Screenwriting with a view #25

Realistic expectations and their importance to your next project

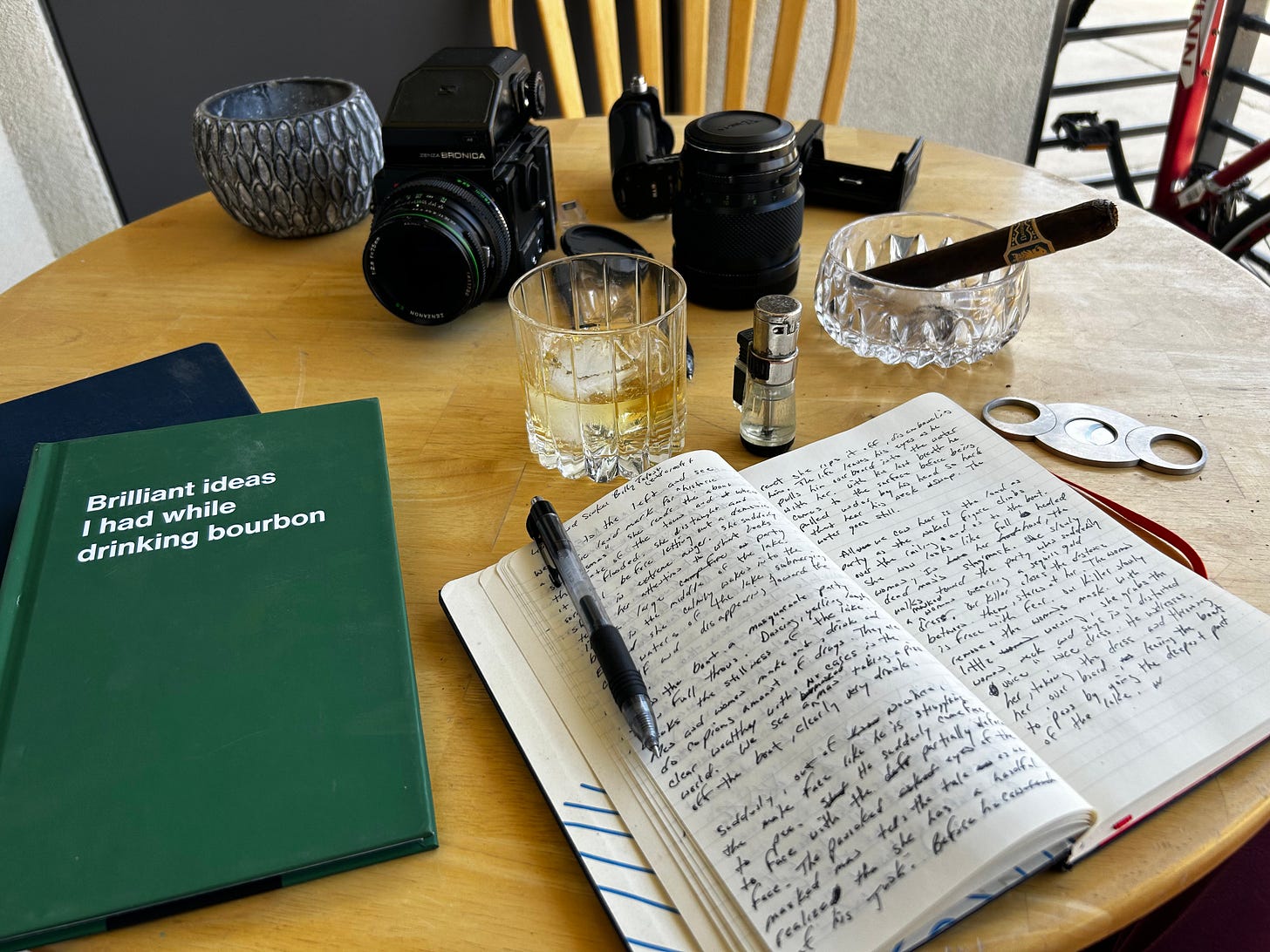

This past weekend was packed, as usual. But I carved out time to sit down with a close friend—someone who’s not only a fellow filmmaker but also further ahead in his career after striking gold early on. I’m not going to name-drop. Not out of secrecy, but out of respect. People in this industry tend to overstep when they find out someone’s door is open. And while I’m protective of that friendship, I’m even more protective of that person’s peace. If you know me well, ask, and I’ll connect you. But for strangers or acquaintances? That path isn’t through me.

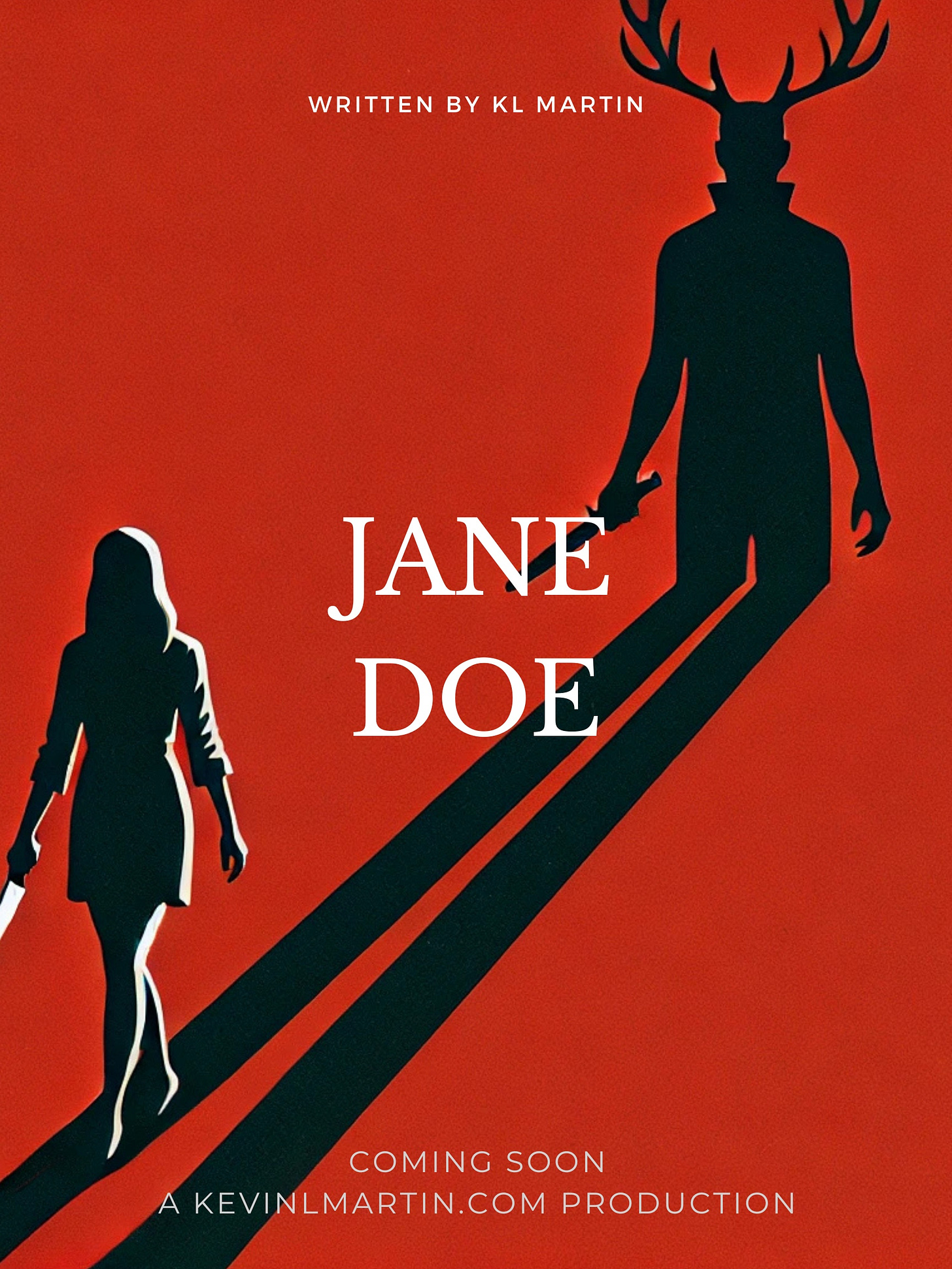

That conversation, though, stuck with me. We talked about Jane Doe—my upcoming horror slasher—and a quiet realization I’d had: I accidentally wrote the script within my means.

Let me explain.

Horror Is Always “In”

Horror never truly goes out of style. It finds its audience, even if it takes a few years. Whether it’s through a cult following or niche appeal, horror has one of the highest return-on-investment potentials in independent filmmaking. Why? Because horror fans show up. And when a story taps into a subgenre that resonates—psychological, slasher, supernatural, body horror—you don’t need $5 million to make it work.

Jane Doe is a slasher set in and around Las Vegas, inspired tonally by Friday the 13th and Coralie Fargeat’s Revenge. I developed it out of a short film I made a year and a half ago called You Should Smile More, which has since done the festival rounds and picked up a few accolades—including my first Best Director win.

But here’s the thing: I didn’t write Jane Doe thinking, “Can I shoot this on a budget?” I just wrote it. It wasn’t until I started breaking down the script—locations, effects, scenes—that I realized: I had written it with a lean budget in mind. I just didn’t know it at the time.

The Philosophy: Writing to Produce vs. Writing to Sell

One thing I preach (and try to practice) is knowing the difference between writing to sell versus writing to produce. If you’re writing a $500,000+ feature with no path to those funds, you’re writing to sell. That’s fine—as long as you know the odds and you’re writing the hell out of it. But if you’re trying to get things made, you need to work within your means.

When I looked at the bones of Jane Doe, it hit me: I could actually produce this. Here’s a rundown of the key locations:

A desert scene with an old car

Two police cars in the same desert

A police briefing room

A strip club locker room and stage (cheatable sets)

A car interior

A parking lot

A basement hallway

The area around Three Kids Mine (or any remote desert spot with signage)

A small office

A few downtown Vegas alley exteriors

The Neon Museum

On paper, a couple of those might sound extravagant. But in practice, they’re accessible. Some through favors. Some through Peerspace. Some through relationships I’ve built. The Neon Museum? I’ve done work with them before. I’m not giving away the playbook, but if I do this right, I could shoot there for next to nothing.

Budgeting

Jane Doe

After running through the script and speaking with my filmmaker friend, we agreed: this could be shot for $30–35K. I’d budget it closer to $40–50K just to be safe. But that’s still extremely reasonable for a feature-length horror film.

The kills in the script are stylish but grounded. There’s nothing overly complex or VFX-heavy. It’s a classic slasher with a tight focus. The script cuts through Vegas like the killer does—lean, deliberate, and fast-moving.

So what happens next? I’m in the final stages of transferring it all into Final Draft. And once that’s done, the goal becomes real: shoot Jane Doe as a low-budget feature.

Being Honest With the Market

I’m not the type to pretend I can greenlight something on vibes and faith alone. Take Craftlace, for example—my LGBTQIA+ dark comedy. While there’s real interest in that story, it would take a miracle to shoot it this year. We’re talking $300K–700K, and the current economic climate doesn’t favor that kind of independent spend. Studios and investors are shifting toward live events and sports—reliable, cash-positive investments.

Will Craftlace happen eventually? I believe so. But not this year.

Jane Doe? That could happen by early 2026. Two years from when we shot the short. Maybe sooner.

What About Pixels?

This one feels real because there’s real investments so I talk about it a lot

Ah yes—The Rise and Fall of the Pixels. That’s my other feature, a road trip dramedy that tracks a misfit crew of aspiring adult performers on a chaotic journey from Reno to Vegas. It’s sharp, funny, and dialogue-heavy. But more importantly? It’s tight. Contained. Most of the action takes place in a van. Fewer locations. Fewer headaches.

That project does have investment already. We’re aiming for preproduction this July/August, with a shoot scheduled for late September. That one’s real—and real soon.

Final Thoughts

Make your short films. Even if people say they’re a waste of money. That’s subjective. Shorts teach you how to finish. They give you a proof of concept. They let you experiment, fail, and succeed in fast cycles.

Make your low-budget features. But do it with clarity. Know what you’re trying to accomplish. Understand that not everything will get made—and that’s okay. Create a list of projects you need to get done and a list of projects that can wait. And when something’s not working, have the self-awareness to step back and reevaluate.

If you’re building your entire identity around one film, then yes, go all in. Move heaven and earth. But if you’re trying to have a career, then make things that are realistic. Write with what you have in mind. And don’t be discouraged if your expensive project doesn’t land—yet.

You’re playing the long game. And that’s exactly what I plan to keep doing.